How on earth could a bulbous Lincoln from the fifties possibly compete with the relatively modern engineering of a 1995 BMW? On face value this seems like a bizarre match-up, with the older car begging to have its lavishly chromed, baroque front end ground into the dust by “the ultimate driving machine.” But these two cars have a lot more in common than one might expect, and in a couple of surprising areas the Lincoln actually excels.

(A rarely seen ad for the Lincoln Premiere – possibly because it was considered racist all the way back in the fifties.)

Buyers were not especially interested in handling back in 1957, Mr. and Mrs. Plushbottom wanted a cushy ride augmented by heaps of chrome and riotous styling that told the world that they were more special, (as well as more fearlessly tasteless,) than their neighbors. Because of this, Ford never promoted its Lincoln as a driver’s car, even though it was carefully engineered to be one – it was, in fact, the BMW of its era. From the period of 1952 to 1955 “Road Race Lincolns” dominated the Carrera Panamericana rallies through Mexico, consistently winning in their class. The race was finally called off in 1955 because of the large number of spectator casualties. Starting at the top of Mexico in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas and working its way to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, the route wove its way through many small Mexican towns. As the race was the most exciting thing going on, townsfolk would hurry out to the main boulevard to watch the cars streak by, at which point they were summarily mowed down. For several years after the race was terminated, Lincoln continued to be a driver’s car, and its characteristics mirror those of the BMWs made years later.

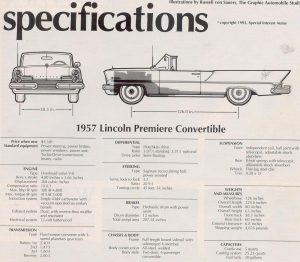

So what do these cars have in common? The BMW utilizes a Macpherson strut front suspension, developed by the very man who was in charge of Lincoln chassis engineering during the fifties. Both cars have power assisted recirculating ball steering boxes with nearly identical gear ratios. The Lincoln’s box gives 3.3 turns lock to lock, the BMW’s is 3.7. (Critics complained that the steering on both cars was a bit too slow and lacked feel.) Both cars came equipped with shock absorbers designed to provide a neutral point for smooth riding over good pavement, and which quickly firmed up when the going got rough. Both cars have close to perfect 50/50 weight ratios. The Lincoln is heftier at 4,538 pounds as compared to the BMW’s 4,145 pounds – portly by today’s standards, but lightweights by the luxury car standards of the fifties and sixties. The Lincoln is also bigger, riding on a 126 inch wheelbase, as opposed to the BMW at 115.4. Overall length on the Lincoln is a whopping 224.6 inches, whereas the BMW’s is 196.2 inches. Despite this, the ’57’s were reputed to handle slightly better than earlier Road Race Lincolns, which were considerably smaller.

Behind the wheel, the cars are remarkably similar. Rides are close to indistinguishable, silky over smooth, well maintained roads, but the moment the pavement starts to give sass, both suspensions immediately firm up and fight back. Both cars corner flat, though lean can be induced in the Lincoln when speeds increase, especially on long gentle curves. Ironically the Lincoln does better in the tight twisties. Going swiftly on a road with plenty of switchbacks, the BMW, with its radial tires, stays glued to the pavement, whereas the Lincoln goes into a four wheel drift when pushed hard. Frightening as it sounds, a four wheel drift is something of a kick, and strangely reassuring to the driver. Rather than feeling like the car is on the verge of flipping, or losing control, the entire vehicle simply slides sideways about six inches to a foot, while remaining completely flat. On twisty mountain roads, both cars are easy to throw around, maintaining their composure at all times. There is a caveat to this, however, in the case of the Lincoln. If the driver is too cautious and moderate in his/her actions, the Lincoln tends to plow. Good handling isn’t achieved unless the driver is aggressive, really giving the big wheel a vigorous swing. I experienced a similar situation when I was allowed to drive a Mercedes-Benz Gullwing many years back.

At the time, I was a salesman at the shadiest used car lot on the west coast, specializing in true classic cars, muscle cars and exotics. The owner expected me to be impressed with the Gullwing, and was disappointed when I was not. The legendary Mercedes didn’t seem all that fast, it’s steering was heavy and it’s handling was plodding – it reminded me of a mid-sixties Ford Falcon. “Don’t be scared of this car,” the owner told me, “you’ve got to be brutal. Just put your foot all the way down and don’t worry – it can handle it.” What the hell, I thought, and did as I was told, stomping on the gas, and heading toward the nearest turn, going into it far faster than I thought was wise. The Gullwing changed its character immediately, handling much more like a late sixties Ferrari or Lamborghini, supercars that drive so well that the driver is merely an accessory.

On the highway, the Lincoln and BMW are again eerily similar, composed and rested at high speeds, with a very slight tendency to wander – typical of motorcars with moderate understeer that can be quickly transformed into moderate oversteer. (The result of that nearly perfect 50/50 weight distribution.) For those who don’t quite get these terms, understeer is created when a vehicle has a lot of weight up front, causing the machine to abhor turning. Shopping carts provide a great example of understeer, as do dogs on leashes who want to sniff grass and resist an owner’s desire that they move along. When a corner is encountered, an understeering car wants to keep going straight. An oversteering car, on the other hand, loves going into turns, sometimes too much. Porches are notorious for excessive oversteering, and if the driver isn’t careful the rear end can break loose and come forward to say hello.

The BMW is most comfortable in the 85 to 90 m.ph. range on the straights, the Lincoln at 70 to 75 m.p.h., and it’s on the highway in particular where the Lincoln gets the edge. The reason is something of a surprise – the Lincoln’s seats are simply much more comfortable.

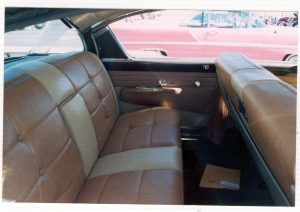

Equipped with a wide bench seat lacking a center armrest, the Lincoln would seem no match for the BMW with its ergonomically correct, reclining buckets.

But in my experience, the BMW produces a nasty back ache after twenty minutes of driving. No degree of fiddling with the lumbar controls or changing positions ever altered this woeful condition. On the other hand, I never got a back ache in the Lincoln and always arrived feeling relaxed and refreshed.

The BMW has an early onboard computer allowing the driver to calculate arrival times, as well as a speed control, a telephone and a means of determining outside temperatures. The Lincoln, on the other hand, could be ordered with a dash mounted, old-fashioned compass, an automatic headlight dimmer, a self-lubricating system for the chassis, and any number of idiosyncratic options. Quaint as these options sound, the easiest way to level the playing field and bring the old Lincoln into the BMW’s high tech realm is with a standard smart phone.

Unlike the BMW, Lincoln offered a great many colors, fabrics and upholstery styles. Some of these choices accommodated those with refined tastes –

While others appealed to those for whom good taste was, at best, an abstract concept.

Good or bad, style was everything in the Lincoln’s day, compensating for Detroit’s lack of engineering innovation. (Lincoln was an exception in this department.) The Lincoln’s front door is simple but very stylish. The manual door lock is next to the interior light. (The power lock switch is on the dash.) The power window controls are awkwardly placed on the dogleg. (Not visible here.)

The BMW’s front door has plenty of storage and real wood trim. Window controls are black plastic and built into the armrest. The door panel itself is molded vinyl with a genuine leather insert for the armrest. The memory seat controls are between the two storage compartments.

Unlike modern luxury cars, the Lincoln’s rear area is sparse, even austere. Partially, this is due to the designers wanting to create a look of modern simplicity. But also, this was a time when modern gadgetry, like power windows and air-conditioning, was considered the ultimate in luxury and more old fashioned pamperings, such as vanities and storage compartments, were passe. (They were also expensive, and the fifties were a time of planned obsolescence and cheap manufacturing.)

In lieu of high tech electronics, the Lincoln offered a vast carry of colors inside and out. (Less than a handful of conservative color choices were available for the BMW’s interior.)

The ride in the rear tells a similar story. No back ache from the BMW, but its rear seat just isn’t as comfortable as the back seat in the Lincoln, or as commodious. However, the BMW has map pockets, cubby holes, map lights, cup holders – all manner of ways to pamper the passenger.

The BMW even has a factory installed first aid kit.

With the Lincoln you get a glove compartment and that’s about it. (One has to go back to the 1930’s to get comparable adornments in a Lincoln.)

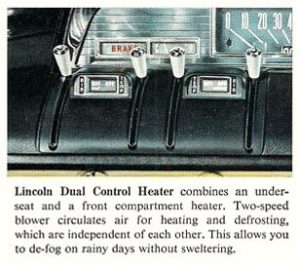

However, one area where the Lincoln shines is with its heater/ventilation/defroster system. Despite having a “sophisticated” climate control system, the BMW’s heating and defrosting characteristics are woeful, to say the least. There might be a sweet spot, a heater, air-conditioning mix that gets everything just right, but I never found it – and I certainly wasn’t going to search for it during the middle of a torrential downpour. What the driver has to put up with is a windshield that fogs up quickly and when the defroster button is pushed, the fan comes on with so much sturm und drang that a hurricane outside the car would seem less raucous. Only a few seconds can be tolerated, so it’s fortunate that the glass is cleared of mist swiftly – that is until the windshield starts to fog up again. As the defroster only has one setting, that being “windborne concussion,” the BMW is best suited for drives in sunny weather.

In contrast, the Lincoln’s system is a joy.

Two matching sets of blower controls and toggle switches allow for easy adjustment where the driver’s side of the car can be heated or cooled separately from the passenger’s side. Defrosting is swift, quiet and efficient. And although there are only two blower speeds, each seems just right. A treat is the old fashioned, fresh air ventilation system, which allows for a trickle of fresh air or a full torrent. Unlike modern cars, where the fresh air always seems tainted and warmed and slightly humid, the air that the Lincoln lets in is so refreshing that one only feels the need for air-conditioning when it’s really, really hot out. Incidentally, both cars have rear window defrosters, and under seat heating vents for both front and rear passengers.

Two matching sets of blower controls and toggle switches allow for easy adjustment where the driver’s side of the car can be heated or cooled separately from the passenger’s side. Defrosting is swift, quiet and efficient. And although there are only two blower speeds, each seems just right. A treat is the old fashioned, fresh air ventilation system, which allows for a trickle of fresh air or a full torrent. Unlike modern cars, where the fresh air always seems tainted and warmed and slightly humid, the air that the Lincoln lets in is so refreshing that one only feels the need for air-conditioning when it’s really, really hot out. Incidentally, both cars have rear window defrosters, and under seat heating vents for both front and rear passengers.

The BMW has a modern, climate control air-conditioning system with outlets in the dash, as is common today.

The Lincoln’s air-conditioning comes from outlets in the headliner.

As I never got my air-conditioning working I can’t comment on which system is best. I have to interject, however, that climate control baffles me. The idea is that you can set your preferred temperature and just forget it, the car will do the rest. In practice, every climate controlled car I have ever encountered requires so much constant fiddling with the temperature settings and blower speeds that I could never understand the advantage over a straight-forward system.

One area where the Lincoln falls short is with its windshield wipers – they’re vacuum operated, need I say more? The theoretical advantage of vacuum wipers is that they can be set to any conceivable speed – the reality, however is grim. Indeed, vacuum wipers work great – until the driver steps on the gas, at which point they slow to a crawl or stop altogether – just what you want in a violent rain storm. The Lincoln has a vacuum tank that’s supposed to compensate for this rather serious flaw, but I never found that it made a damn bit of difference. The BMW’s wipers are modern, competently electric, and have a multitude of settings. Ironically, the first set of wipers had to be replaced on my folk’s 740I. (As did the original transmission.) The wipers were a special kind designed to work efficiently at very high speeds – but the springs used to hold them tight against the windshield were so strong that the wipers actually ground dirt into the glass – as a result the entire windshield had to changed. The new, “less efficient” wipers worked just fine.

In the braking department, the BMW is the clear winner. Its panic stopping distance from 60 m.p.h. in 128 feet is a lot better than the Lincoln’s, which I’m going to guess is about 150 feet – the luxury car standard in those days. The BMW has disc brakes, the Lincoln comes with drums all around and no ABS. Under most driving conditions, the Lincoln is okay, its power booster is powerful and it stops well enough three or four times until the brakes start to fade. Fortunately, the brakes are not prone to fade under regular driving conditions, only if you’re doing a lot of squealing stops from high speeds. All the same, the BMW is far more capable and reassuring in this area.

Both cars have electric windows all around and power door locks – though the Lincoln’s only lock, unlocking has to be done manually. (It was Detroit’s first year for this feature.) Each car comes with power seats, which go up and down, forward and back and also tilt. The Lincoln has no reclining backrest, however, while the BMW also has a memory seat feature, which remembers three driver settings. (A feature pioneered by the 1958 Cadillac Eldorado Brougham.)

Not surprisingly, trunk space in the Lincoln is far greater than the BMW’s. With the Lincoln, it would be easy to smuggle a full family of four through any border.

In the BMW you could only get through a rather smallish mother and her daughter.

The engine compartment of the Lincoln is typical fifties – disorganized and aesthetically challenged. Despite the car’s enormous size, the space for the motor is cramped and repairs are not especially easy to execute.

In comparison, the BMW’s engine compartment is very pleasing to look at – though many of the decorative panels are of plastic. Servicing is also easier than in the Lincoln – to a point. Anything serious is beyond the means of a backyard mechanic.

One “luxury” that the Lincoln offered was a variety of body styles. Besides two sedans there was a coupe and a convertible.

The BMW, on the other hand, had a long wheelbase version, and a V-12 known as the 750IL.

So, let’s go for a ride.

Starting with the Lincoln, the first thing you notice is how big it is. ’57 Lincolns are mercurial in appearance. From certain angles they come off as hulking and strange, especially if paint is faded and chrome is tarnished.

From other vantage points they are dramatic and thrilling, sleek and magnificently sculptural.

More than most cars, condition makes all the difference. In photographs, they don’t look all that much like luxury cars. Luxury cars by nature are restrained, imposing, intimidating. Tinted glass, or large blind rear quarters should conceal and protect passengers, hinting at a rarefied world off limits to those who aren’t wealthy and privileged.

With its expansive greenhouse, the ’57 Lincoln puts its occupants on display, and all sense of mystery or exclusivity is dissipated.

With its expansive greenhouse, the ’57 Lincoln puts its occupants on display, and all sense of mystery or exclusivity is dissipated.

Worse, the tail fins, the silly “I’m rich” logos, the two-toned upholstery and flamboyant colors so popular in the fifties are the opposite of intimidating. The lack of skirts for the rear fenders add a sporty, plebeian touch to the Lincoln, which further diminishes its luxury car image. The fact is, most expensive American cars from the fifties fail to be intimidating due to comparable styling choices. I remember watching The Man From U.N.C.L.E. as a kid and noting that a lead baddie lost nearly all his mojo if he transferred from a ’65 Lincoln or Imperial, to a ’55 Cadillac limousine. In the sixties Imperial he was “Doctor Evil:”

Likewise the Lincoln.

while in the fifties Caddy he was instantly demoted to “Louis The Louse:”

Ironically, the only cars I can think of from the fifties that truly looked like luxury cars were the ’56 Lincolns, and the Continental Mark II.

The Continental was restrained and sported a true blind rear quarter, while the Lincoln, with properly skirted rear fenders and a simplicity of design that greatly outclassed its competitors, was an oasis of relative refinement in an unrepentant landscape of girth and bling.

In person, the ’57 Lincoln presents a far more flattering visage. Its sheer size, a platform for silky paint covering massive, sculptural shapes, and lots and lots of chrome leaves the observer thinking “Wow! People got all that for their money? Amazing!” One isn’t buying a car as much as a full Broadway musical on wheels- not a vehicle for introverts. The Lincoln also seems a good deal lower and sleeker in person, even tasteful, particularly evident if parked next to its main competition – a 1957 Cadillac.

In contrast, the Cadillac is unpleasantly plump and dumpy, its use of chrome random and desperate.

Coming closer and and activating the sleek, fifties style door handle, one is struck by how heavy the door is. My grandmother had a ’62 Continental, and if she parked on a slight incline, and had to push the door upwards to exit, she couldn’t get out of the car. I wonder how many wealthy old ladies have been trapped in their Lincolns over the years?

The interior of the Lincoln appears sparse for a luxury car, and not terribly lavish.

The sense of touch, and a closer look, quickly dispels this first impression. The door panels, for instance, though vinyl, are upholstered, not stamped, and all the fixtures are heavy and substantial and nicely detailed. Even the controls for the heater and defroster, which appear to be plastic, are actually painted metal. When plastic is used, on the shifter knob for instance, it seems an aesthetic choice, not one of economy. Fit and finish is very good and the leather seats are exceedingly smooth and comfortable.

There are lapses, the front kick panels lack stitching to match the door panels, and the loop carpeting, so popular in the fifties, comes off as cheap rather than chic.

Getting behind the wheel is easy, so long as you take care not to bang your knee on the dogleg. Immediately you’re aware of how different this car is from modern vehicles – it’s a whole different universe. The car feels very wide, (because it is,) yet despite a vast acreage of glass, the windows are narrow – looking through the windshield gives the feel of wearing a baseball cap with the visor pulled down low over the eyes. This is no mere illusion, Lincoln offered an optional prism, which attached to the rear view mirror and allowed the driver to see when a stoplight changed without having to crane his/her head.

In front of you is a handsome, space-age style dashboard with a lot of bling by today’s standards – by the standards of its time, however, it was quite restrained. In contrast, the dash for a 1957 Cadillac shows what a prosperous fifties motorist was more accustomed to.

The interior of the Lincoln comes across as too flashy for a bank president, but not sparkly enough for a successful entertainer – one feels more like a record producer, or with the car’s definite Las Vegas flavor, a professional gambler.

The padded dash, more common on the 57’s, was an industry leader. In 1955 Ford led the way by being the first auto company to promote safety, offering seat belts, padded dashes and concave steering wheels. These features were resisted by the marketing department, which warned that talking up safety would spook buyers, who didn’t want to be reminded that their cars were inherently dangerous. The naysayers felt themselves proved right when Ford and Mercury sales took a small dip in ’56. Lincoln, however, bucked the trend, seeing its sales rise – mostly due to its dramatic new styling.

Put the unusual, rectangular handled key in the ignition, press the accelerator pedal to the floor to activate the automatic choke, release it, and turn the key. After the distinctive high-pitched growl of the Ford starter, familiar to viewers of old Perry Mason episodes, the car comes instantly to life. It’s good to let the engine warm up for a minute or two, then tap the gas and the engine swiftly settles down to a very quiet, unobtrusive idle, the exhaust burbling like an old motorboat. In front of you, the minimal gauges are not easy to read, due to the white letters on silver. (Fifties critics didn’t like this.) Idiot lights were in vogue so the Lincoln has a speedometer, a clock, a gas gauge, a temperature gauge and that’s all. However, the oil pressure light and the ammeter light flicker when things aren’t quite as they should be, and this imparts some information – also these lights fade away when the engine is revved, (unless something is really wrong.) The gas gauge also has a red warning light to let you know when the tank is low, and there’s a light to warn if a door is ajar.

The shift lever is on the steering column, (another remnant from the past,) but, mercifully, the quadrant is laid out in the modern sequence with “R” following “P” for park. (Early automatics had “D” following “P”, which resulted in far too many drivers, ready to back out of their driveways, plowing into their garage doors instead.)

In preparation to shifting, one steps on the extra wide power brake pedal and is confronted with yet another foreign sensation – the pedal barely gives, it’s like stepping on the floorboard. (This is assuming that the brakes have been properly adjusted, something that had to be done by your mechanic in the bad old days.) Select your gear, and you’re off.

Backing up the enormous beast is a lot easier than one might expect due to an unexpected feature – the tail fins. Because of the fins, and the wraparound rear window, it’s extremely easy to gauge exactly where the car ends – there’s simply no guessing. The shark-like shrouds over the front lights are equally informative – all that crazy styling turns out to be weirdly practical.

The fins are useful in other ways, it’s been theorized that they work like a spoiler and keep the rear on an even keel at high speeds, (I’m inclined to believe this,) and there’s no missing the Lincoln’s over-sized taillights – or stoplights during the day.)

The extra-large backup lights in the rear bumpers are also very bright and useful. (Except in a collision, of course – though I wouldn’t want to go up against that bumper in a modern Toyota.)

From the rear, the BMW’s styling is quite a bit more restrained.

Out on the road, the Lincoln continues to feel, well, big. The ride is quiet, the engine barely audible. Road feel through the steering wheel is excellent, despite what the critics had to say. The kind of steering feedback that automotive writers gush over is generally appropriate to a sports car, too harsh for a luxury car. Both the Lincoln and the BMW hit the balance just right, enough road feel so that the driver feels in control and well-briefed, not so much as to make the driving experience unpleasant and wearing. Additionally, steering is positive and responsive. What exactly does this mean? Sticking a shovel into fresh earth gives a positive, responsive feel. The effort expended is directly proportional to the amount of dirt extracted, one can feel, through the shovel’s handle, exactly how much resistance the packed earth is kicking back with. There’s a direct correlation between the movements of the shovel and the earth that is moved. The experience ceases to be positive when the shovel is raised into the air and the dirt is tossed to the side. Maybe all the dirt in the shovel will go flying, maybe only half of it will; and it won’t necessarily land where it’s supposed to. Similarly a car’s steering is not responsive when there’s too much slop in the system, usually from wear. Overly-assisted power steering creates an additional, disembodied, non-responsive feel, as can weird suspension geometry, where the front wheels seem to have a mind of their own. The positivity of both the Lincoln and the BMW is like sticking a shovel in smooth, thick mud – one feels a direct connection between the turn of the wheel and the response of the car, but the feedback through the wheel is silky and easy.

Coming to a stop, the brake pedal continues to feel unyeilding, yet the car deaccelerates smartly and with little effort – assuming the driver uses a light touch. Too much pressure and the big car will literally come to a screeching halt.

Entering a freeway is no problem, stomp down on the gas and the big car surges forward with a wonderful, turbine-like smoothness. There is no problem whatsoever keeping up with modern traffic, and all that glass allows an unhampered view in every direction. (Though nausea can ensue if the driver becomes overly fascinated with the distorted corners of the wrap around windshield.)

On a fast road with sharp curves, the Lincoln heels over – more than I care for. That is until I look at the speedometer and realize that I’m going ten to fifteen miles per hour faster than I thought. This happens a lot, taking a turn on a challenging road like highway 17 out of Santa Cruz, for instance, and assuming that I’m doing 55, then discovering that I’m actually doing 70. This is a characteristic of big, old luxury cars, the tendency to suppress the sensation of speed. Nonetheless, handling remains top notch, and even when one enters a turn faster than expected, the big car can be powered through it, quickly regaining its equilibrium.

If the Lincoln has a real Achilles heel in terms of handling it’s from a surprising source – the lack of an intermediate speed hold. Going up hill is fine, the Lincoln tears exuberantly and competently through even the tightest turns, but when heading downhill the automatic transmission shifts into hi and can’t be dissuaded from staying there; the only alternative is to downshift to lo, which is only appropriate for speeds under 15 m.p.h. Locked in hi, the Lincoln swiftly gets away from the driver, and riding the brakes until they fade into oblivion is the only option for an aggressive driver. What an amazing road car the Lincoln would be if it had been offered with a manual four speed transmission.

It’s always a disappointment for me to pilot the Lincoln back home, it’s such an entertaining ride. And despite its over the top styling, or perhaps because of it, I find myself constantly sneaking peeks of it as it sits in the driveway.

Like the Lincoln, the BMW’s door feels heavy to open, but not to the same degree, it’s like comparing Seth Curry to Hulk Hogan. The outside handle is recessed and painted, far more conservative than the Lincoln, but still expensive in look and feel. Getting behind the wheel is also easy, and there’s no fifties dogleg to bang one’s knee against. The cabin of the BMW is best described as high-tech cozy – surrounded by soft leather and gleaming touches of genuine wood, one feels like the villain in a James Bond movie.

As with the Lincoln, instrumentation is minimal, consisting of a speedometer, tachometer, gas gauge, water temperature gauge and a peculiar instrument that does an inept job of registering fuel efficiency. Radio, and tape deck controls controls are hidden behind a wood covered plastic slab in the center of the dash, which raises elegantly with a slight inward push. Also included are setting for the CD player, located in the trunk. Air conditioning and heater controls are below, but out in the open. There are cubbyholes and hidden cup holders and sliding consoles galore, one could spend hours discovering all the little secrets in the car’s interior.

The starter turns over busily and quietly, sounding not unlike a racing sewing machine and the engine comes quickly to life. It’s not necessary to step on the gas to set the choke and the engine settles into a smooth idle without coaxing. There’s a lot to be said for modern fuel injection and electronic ignition. The wooden gearshift knob is in the center consul, rather than sprouting from the steering column, and there are a variety of gears to choose from, including a sport selection for furious driving. Seats are power assisted with three possible memory selections, (for three separate drivers,) and the steering column is adjustable, a feature that Lincoln wouldn’t get until 1961.

On the road, as stated earlier, road feel, ride and handling is eerily similar to the -57, in fact, if fitted with the Lincoln’s large, thin plastic steering wheel, Al Pacino’s blind character in Scent Of A Woman would be hard pressed to know what car he was driving. One giveaway is the BMW’s tuned exhaust, which imparts the car with a classic sports car sound, and the German car’s automatic transmission makes its presence known almost immediately. Despite some early bugs, (my folks’ transmission had to be replaced within the first five thousand miles,) this unit is simply magnificent, exceptionally responsive and intelligent, with a remarkable ability to pick the perfect gear for any driving situation. Acceleration is brisk, and almost any speed under 110 can be accessed effortlessly. The BMW’s top speed of 135 m.p.h. is considerably higher than the Lincoln’s 112 m.p.h. Though a 0-60 time of 8.0 seconds is not staggeringly better than the Lincoln’s 11.2 seconds.

After driving the Lincoln, the BMW’s brakes feel spongy, but they do the job exceedingly well, stopping quickly and without any tendency to lock up or fade.

Pushed hard, the BMW handles better than the Lincoln, with less demanded of the driver. Its steering seems quicker, despite requiring nearly identical turns lock to lock – the BMW’s tighter ratio makes the difference here. Nonetheless, these performance edges on the BMW’s part are not so dramatically superior to the Lincoln that a race up a winding mountain road couldn’t be won by the older car if it was piloted by a more skilled driver.

So which is the “ultimate driving machine?” Frankly, neither. Both are very good, fine handling luxury cars, which strike an excellent balance between sportiness and comfort. Both are reliable and well made – but not ultimates in any way. My old ’37 Cadillac rides better than either of these two marques, and the BMW’s excellent handling is hardly in the Ferrari or Lamborghini league. All the same, these two motorcars were cutting edge in their day, achieving a standard of engineering excellence that their competitors were generally unable to match.

|

GENERAL |

|

| Make and model |

BMW 740i |

| Importer |

BMW of North America,Woodcliff Lake, N.J. |

| Location of final assembly plant |

Dingolfing, Germany |

| EPA size class |

Midsize |

| Body style |

4-door, 5-passenger |

| Drivetrain layout |

Front engine, rear drive |

| Airbag |

Dual |

| Base price |

$57,900 |

| Price as tested |

$64,720 |

| Options included |

Premium sound system w/CD, |

| Ancillary charges |

Gas guzzler, $1000;destination, $470 |

| Typical market competition |

/JX12,Lexus LS 400, Mercedes-Benz |

|

DIMENSIONS |

|

| Wheelbase, in./mm |

115.4/2931 |

| Track, f/r. in./mm |

61.1/61.7/1552/1567 |

| Length, in./mm |

196.2/4983 |

| Width, in./mm |

73.3/1100 |

| Height, in./mm |

56.5/1435 |

| Ground clearance, in./mm |

4.7/119 |

| Manufacturer’s base curb weight, lb |

4145 |

| Weight distribution, f/r % |

51/49 |

| Cargo capacity, cu ft |

13.0 |

| Fuel capacity, gal |

22.5 |

| Weight/power ratio, lb/hp |

14.7 |

|

ENGINE |

|

| Type |

V-8, DOHC, liquid cooled, castaluminum block and heads |

| Bore x stroke, in./mm |

3.50 x 3.15/89.0 x 80.0 |

| Displacement, ci/cc |

243/3982 |

| Compression ratio |

10.0:1 |

| Valve gear |

DOHC, 4 valves/cylinder |

| Fuel/induction system |

Multipoint EFI |

| Horsepowerhp @ rpm, SAE net |

282 @ 5800 |

| Torquelb-ft @ rpm, SAE net |

295 @ 4500 |

| Horsepower/liter |

70.1 |

| Redline, rpm |

6500 |

| Recommended fuel |

Premium unleaded |

|

DRIVELINE |

|

| Transmission type |

5-speed auto. |

| Gear ratios | |

| (1st) |

3.55:1 |

| (2nd) |

2.24:1 |

| (3rd) |

1.54:1 |

| (4th) |

1.00:1 |

| (5th) |

0.79:1 |

| Axle ratio |

3.15:1 |

| Final-drive ratio |

2.49:1 |

| Engine rpm,60 mph in top gear |

1900 |

|

CHASSIS |

|

| Suspension | |

| Front |

MacPherson struts w/double-pivot lower |

| Rear |

Multilink, coil springs, gas-pressureshocks, anti-roll bar |

| Steering | |

| Type |

Recirculating ball, variable power assist |

| Ratio |

16.9:1 |

| Turns, lock to lock |

3.7 |

| Turning circle, ft. |

38.1 |

| Brakes | |

| Front, type/dia., in. |

Vented discs/12.8 |

| Rear, type/dia., in. |

Solid discs/12.8 |

| Anti-lock |

Standard |

| Wheels and tires | |

| Wheel size, in. |

16.0 x 8.0 |

| Wheel type/material |

Cast aluminum |

| Tire size |

235/60HR16 |

| Tire mfr. and model |

Michelin MXV4 |

|

INSTRUMENTATION |

|

| Instruments |

150-mph speedometer; 7000-rpm |

| Warning lamps |

Seatbelts; airbags; check engine; |

|

PERFORMANCEAND TEST DATA |

|

| Acceleration, sec | |

| 0-30 mph |

3.4 |

| 0-40 mph |

4.7 |

| 0-50 mph |

6.3 |

| 0-60 mph |

8.0 |

| 0-70 mph |

10.3 |

| 0-80 mph |

12.5 |

| 0-90 mph |

15.3 |

| Standing quarter mile | |

| sec @ mph |

16.1/92.8 |

| Braking, ft | |

| 30-0 mph |

34 |

| 60-0 mph |

128 |

| Handling | |

|

Lateral acceleration, g |

0.87 |

| Speed through 600-ft | |

| slalom, mph |

61.4 |

| Speedometer error, mph | |

|

Indicated |

Actual |

|

30 |

28 |

|

40 |

37 |

|

50 |

47 |

|

60 |

57 |

| Interior noise, dB | |

| Idling in neutral |

45 |

| Steady 60 mph in top gear |

61 |

|

FUEL ECONOMY |

|

| EPA, city/hwy., mpg |

16/24 |

| Est. range, city/hwy., miles |

360/54 |

1957 Lincoln Performance Figures

0-30 4.3 seconds

0-45 7 seconds

0-60 11.5 seconds

0-80 19.2 seconds

30 to 50 4 seconds

50 to 80 12.2 seconds or 10.4 seconds

112 m.p.h. Top speed

11 m.p.g. Average