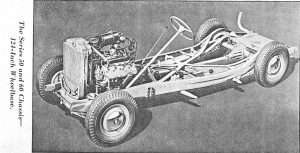

For decades Cadillac’s advertising catchphrase was “Standard Of The World,” and rather than being a pompous boast, it was a simple statement of fact. No Automotive manufacturer was the source of so many iconic engineering breakthroughs. Cadillac pioneered the self-starter, the synchromesh transmission, independent suspension, the automatic transmission, automotive air conditioning, multi-cylinder engines, thin wall casting procedures essential for modern automotive power plants; the list goes on and on. Many of these engineering breakthroughs were created exclusively by Cadillac, others were developed simultaneously with other automakers, but were aggressively put into service by Cadillac, so that they consistently led the industry. (Rolls-Royce, lacking Cadillac’s resources, were content, from the late thirties on, to license Cadillac engineering and produce what was essentially a painfully complex, beautifully made, second rate Cadillac.)

Gilding the lily, Cadillac maintained a standard of quality that buyers could count on, and which prevented their engineering breakthroughs from being put into service until they were thoroughly tested and reliable. I can personally attest to this fact. At around 300,000 miles, my engine had finally had enough. Leaving San Francisco on highway 280, I heard a bang and my old Cadillac immediately lost power. I pulled over, lifted the hood and expected the worst. No smoke, flames, or holes in the block, but the motor was visibly vibrating and sounded like it was chewing walnuts. I knew a major repair was in order, but it was late, the car was still running, and even if the engine blew up, would the cost to fix it really be any more than it was already going to be? With all the wisdom of a twenty-two year old, I decided to soldier on. I drove in the slow lane at about twenty-five miles an hour and finally arrived home after midnight – the car had gone about thirty miles since whatever terrible thing that had happened had happened. The next day, I decided to pull the heads to see how bad things really were.

At least one valve was bent and two of the pistons on one side looked like somebody’s dog had been chewing on them. Awful, but fixable. Yet even in this condition, the car had gotten me home. I’m a big fan of Lincolns, but I have to admit that every Lincoln I’ve ever owned managed to leave me stranded, at some point, out in the middle of nowhere. My ’37 Cadillac never did – like Gunga Din mortally wounded and crawling to the summit to sound a warning, it always got me home before dying.

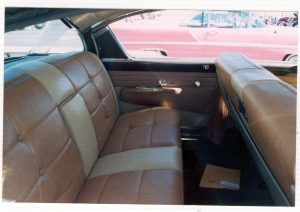

So what’s it like to drive one of these machines? I can only speculate on what a ’37 Cadillac was like when new, based on the years I spent behind the wheel in mine as it underwent myriad forms of restoration, and my experiences driving very low mileage, original Cadillacs from the period. Climb behind the wheel and two things standout immediately, how sublimely comfortable the front seat is, and how narrow and intimate is the front compartment.

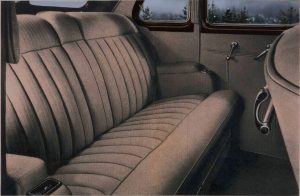

With Marshall springs and cotton padding, the overstuffed front and rear seats of these cars are far more comfortable than anything to be found in a contemporary luxury car. Better, still, the old ads about arriving at your destination feeling refreshed and relaxed were not exaggerating – I never got a back ache or any kind of fatigue behind the wheel of my Series 60, and it’s the perfect car if you’ve got kids. Put them in the back seat, and they’ll be asleep after twenty minutes. (No, not because of a carbon monoxide leak.) There’s just something about the slow, musical hum of the engine, the gentle, vaguely nautical ride, and those super comfortable seats.

Unlike modern cars, the windshield, in fact, all the windows, are very small, creating a cozy ambiance – but vision is not compromised – at least not looking forward. Seen through that narrow windshield, far, far away is a shining chromed goddess with glass wings – pointing the way and giving the impression that this motorcar has someplace very important to go. An absurdly long hood is another thing one no longer finds in a modern car and more’s the pity.

Assuming this Cadillac Series 60 Sedan is brand new, one is immediately aware of the quality – dusky taupe patterned broadcloth seats, and smooth broadcloth door panels, combine with dark woodgrained garnish moldings to create a very formal, almost corporate environment. Heavy, brightly chromed door handles and window cranks seem to float in space, and the gleam of the woodgrained metal window surrounds create a serious and expensive feel.

Deliberate simplicity of design is a trademark of most luxury cars of the thirties, where modernity becomes a showcase for the finest materials. Even the chromed Phillips head screws that hold the windshield and rear window moldings in place provide unexpected dashes of elegance, as do the patterned pipings on the seats, and rear armrest, made of the same material as the assist straps and windlacing around the doors.

This intense attention to the subtlest details conspire to create an atmosphere of great elegance. Sadly, when chrome tarnishes even a little, broadcloth fades, and false wood begins to peel and dim, this magical effect is lost. It can only be reclaimed by the sort of perfect – dead-on accurate restoration that is rarely seen today.

Starting the car is easy – even by today’s standards. And the starkly simple dashboard reinforces the notion that this will not be a hard car to drive. In fact, the dash, like most 30’s dashes, is a marvel of deception, packed with hidden complexities. The driver gets complete instrumentation, for instance, no idiot lights. There are more settings for the outside lights than in a modern car, and the glove compartment is so deep you can bury your arm in it up to your elbow. A delightful feature is the map light, which looks like a second cigar lighter.

Pull it out and one discovers a long cylinder with a hole in the side that emits light. The genius of the device is that the cylinder can be rotated 360 degrees so that light can be shown all around the cabin – up down – sideways. Why this feature didn’t catch on industry wide is beyond me. There is also a hand throttle, which can be used as a primitive cruise control by a brave driver.

The fact is that cars of the twenties and early thirties were demanding to operate. One had to set chokes and throttles, retard sparks, double clutch, pump the brakes – on and on. As a result, and I confess this is my theory, dashes were designed to look as simple as possible so the driving experience would come off as easy, friendly, and not nearly as intimidating as it truly was. By the mid-thirties cars had gotten a lot more user friendly, but the old perceptions persisted and had to be countered – especially with more and more women driving. In the Cadillac of 1937 the bad old days were very much on their way out. Not only was the front seat sinfully comfortable, but it was also adjustable – backwards and forward only – but that was a feature that many cars still lacked. Regardless, the designers of the car got everything just right – the armrest is perfectly placed, the steering wheel at just the right angle, all controls easy to reach.

Put the key in ignition in the center of the dash and switch on the juice. Depress the clutch, put the car in neutral to reduce strain on the engine and press the starter button to the left of the steering wheel.

This is one of the first cars with an automatic choke, as well as a spark advance, so nothing more is needed and the car starts immediately. UNLESS, it’s been sitting for a week or so. In that case, the six volt battery will crank the power plant so slowly that complete electrical death seems imminent. Somehow, the motor just keeps grinding away and grinding away and twenty to thirty nerve-wracking seconds later, (the Cadillac’s owner’s manual actually states that it can take that long,) the beast roars to life.

Backing out of a driveway is something of a challenge because the car is high and the windows, particularly the rear window, are small. As a result, low things like hedges, or small frolicking children are hard to spot.

Limited review vision aside, the car remains easy to operate. The clutch is light and engages right away. The floor mounted shifter requires little effort to operate, but throws are long and there’s a fair mount of wiggle-waggle. This slack, however, is not unwelcome, it adds to the feel that the car is friendly and forgiving. Reverse is up and toward the driver, first down and close. Second is high and away, and third is down and also away, a traditional H pattern. Occasionally, things are resistant to going where they belong, in which case it is helpful to bump second.

If the car is slightly out of position before moving, a steering correction is not impossible. With the correct four ply tires, it takes effort, but not an excessive amount to move the wheel when the car is at rest. Once moving, steering lightens up considerably, and at any speed over 5 m.p.h. steering effort is so light as to rival modern power steering units. In fact, over, say, 30 m.p.h., steering effort is actually lighter than on a modern car with power assist.

It’s wise to let the engine warm up, but assuming that we’re in a brand new 1937 Cadillac, studying the gauges is important. Not only should the temperature gauge move to the one quarter position, where it will remain seemingly for eternity, but a constant glance at the oil pressure gauge reassures the driver that the motor has not died. Why is this an issue? Because the engine of a brand new 1937 Cadillac is so smooth and so quiet that once the idle settles down there is almost no sensual clues that those eight cylinders are in motion.

Okay, let’s go. Depress the clutch, put the car in reverse, rev the engine a little, let out the clutch slowly, crane your head to look over your shoulder and back out the drive. With any luck, you reach the street without flattening any children or maiming any pedestrians, and you straighten out, put in the clutch, bump second, put the car securely in first and you’re ready to take on the world. The Cadillac accelerates smartly, its no hot rod, but it has plenty of power. In some very unscientific, seat-of-my pants acceleration tests, I determined the Series 60’s 0 to 60 time to be 16 seconds. (Interestingly, this is the same that I estimated for a friend’s 1938 V-16.) Ironically, the limiting factor is not engine power, but the transmission. Though very popular with hot-rodders in the 50’s, the Cad’s three speed is slow to operate by modern standards. If I had really practiced with it, and been somewhat less genteel, I imagine I could have gotten the 0-60 time down to about 12 seconds. In contrast, over 50 the old girl really picks up her skirts and takes off. I’m guessing that the long stroke is the reason why – slow to get going, once the engine builds momentum – watch out! As a result, acceleration over 50 m.p.h. is very brisk and is comparable to contemporary cars. Driving back and forth between San Francisco and Los Angeles in the ’70s I loved going down Highway 1. Tourist traffic could be a headache, and in the Cadillac I’d often effortlessly pass a line of five cars at a time. Cadillac listed the top speed of the 1936 Series 60, which had the old transmission and 125 hp, (as opposed to the 37’s 135,) at 92 m.p.h. My experience suggests that the peak speed of a ’37 Series 60 would be higher, especially with the aid of modern gas. In fact I read an account of a Canadian back in the thirties who bought a ’38 LaSalle, had 1/16 milled off the heads, a 2.9 crown wheel and pinion cut, and then installed a special set of valves and springs. The result was a zero to sixty time of 10.2 seconds and a top speed of 107.2 m.p.h. On good roads he could cruise all day at 85-90 mph. This hardly seems far-fetched, on the freeway my unmodified, high mileage Cadillac seemed happiest cruising at 65 m.p.h., though a constant 70 wasn’t much of a stretch.

The transmission is pretty quiet, there’s very little of the sharp whine associated with cars of the period – instead, the driver is rewarded with a wonderful, deliciously purposeful “whoosh” as the car gains speed. Up ahead is a stop sign and so it’s time to test the brakes. The pedal is right there, no play, minimal travel, and moderate effort is required, (only the big Cadillacs have power assist.) By moderate, I mean moderate, and after a few stops, the driver forgets that the brakes lack the help of a servo. The other surprise with the brakes is that they STOP – no fuss, no fade, no locking up, the old adage of “stopping on a dime,” immediately comes to mind. In 1937, Packard tested their new light eight against a 1937 LaSalle, which was mechanically nearly identical to the Series 60, and only weighed about 100 pounds less. Packard reported, with all the smugness that they could muster, that the LaSalle’s stopping distance from 60 was no better than the Packard’s at 128 feet. Translation: it was no worse. 128 feet from 60 is what modern cars do.

Brake fade is something I don’t remember, if I ever experienced it it was minor. Everything was over-engineered back in the thirties, and it wasn’t until after the war that things began to slip. Prior to 1940 designers were consumed with making the product better each year, after 1945 they were focused on providing what the customer expected at the least cost to the factory. As a result, quality took a hit, and the horror stories about frightening handling and dangerously fading drum brakes began. I can say from years of experience that the brakes in my old Cadillac never let me down, to this day they inspire more confidence than the brakes on my ’97 Ford F150, and are far superior to the brakes on Cadillacs and Lincolns from the 50’s and 60’s. (Brakes on those cars, especially Lincolns, did get pretty good in the late 60’s and the 70’s, however.)

Driving around town, the ride on the series 60 seems pretty good, but nothing to write home about. It’s only when you go over the same stretch of road in a new car that you realize how amazingly good the old Cadillac’s ride actually is. In the a modern car several blocks of pavement, which you assumed, behind the wheel of the old Cadillac, was fairly smooth is suddenly filled with ruts and bumps and potholes you never knew were there. So why wasn’t the old Cadillac more impressive the first time around? The reason is because the driving experience in a series 60 is more akin to a sports car than a luxury car. The driver has to attend to a manual transmission, which requires constant shifting, after regulating engine speed, and operating the clutch. The engine is quiet, but still very mechanical – the sounds it makes are wonderful and captivating, so you’re aware of them. Finally, turn indicators weren’t offered on American cars until 1938. Because of this, around town, the driver’s window is going to be down to allow for manual hand signaling, with only the left hand available to steer and shift. With all this going on, the ride goes unnoticed, overpowered by a lot of busyness behind the wheel. On the freeway, it’s a different story. Assuming that traffic is light, and the windows are up, the engine becomes a subdued hush, barely heard, and the ride is so smooth and steady it’s like floating. Occasionally, this smoothness becomes unsettling – I would take to moving the wheel rapidly back and forth, (while staying within my freeway lane,) just to be sure that I hadn’t lost traction due to a tire about to go flat. A friend dubbed this maneuver “rumba car.” It’s a check I rarely feel the need to exercise with a modern car – even the smoothest riding – because today’s smooth rides simply aren’t as smooth as yesterday’s.

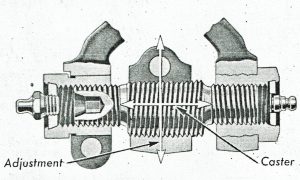

Handling is contemporary. As previously stated, steering is light and not unduly slow: three and a half turns lock to lock. Lean on turns is minimal and road feel is a perfect balance of informative and subdued. There is a certain caveat to the easy steering, however, because the system is manual. Power steering is a great equalizer, suppressing input from the road as it assists. In a way, it’s an additional shock absorber. Manual steering, on the other hand, has greater road feel. In the case of the Cadillac, a heavy, well-engineered car, shocks and unpleasant kick backs from the road are barely felt. But when the car turns, changes in steering geometry and weight shifts express themselves as increases and decreases in steering effort. These fluctuations are subtle, but they can make the steering feel less effortless than it actually is. On the other hand, it’s one of those sensual qualities that causes the Cadillac to feel more like a sports car than a stereotypical luxury barge. A unique characteristic of Cadillacs from this period is that steering wheel return is aggressive, for lack of a better word. On my Series 60 return wasn’t unduly strong, unlike a friend’s 1938 V-16 where, coming out of a turn, the wheel returned to center so fiercely that I felt I should check my palms to see if they were smoking.

One thing I should add, in the 150,000 miles I put on the car myself, I can never recall enduring the kind road bullying that old cars are so often accused of being subjected to. The front wheels of my old Cadillac had no tendency to be pulled from one irregularity in the pavement to another; it always tracked straight and clean.

On the highway the Cadillac is nearly silent, the engine a subdued hum, droning rhythmically in the manner of an old propeller plane. Where the Cadillac really shines, however, is on a twisty mountain road. This is a car that exhibits moderate understeer, in other words the old beast wants to go in a straight line and doesn’t like to be coaxed away from its course. This is great on a freeway, where an understeering car settles down to a very stable ride and is disinclined to wandering. On curves though, a car with a lot of understeer will tend to plow. Moderate understeer is a different story – more manageable, and more tolerant of sharp turns taken at high speed. Combined with the remarkable flexibility and low speed torque of the 346 V-8, mountain driving is a pleasure. The Cadillac has no problem accessing steep grades in high, but second gear is the best choice for switchbacks. Because the motor is low revving, second gear is not the strained roar that it can be in a contemporary car, and the Cadillac seems to enjoy eating up the pavement at a very swift velocity. Where the car really comes into its own is on down hill grades – the engine is so powerful, and so flexible that braking is a mere afterthought – it’s easy to go down hill for miles quickly and in full control, without stepping on the brakes once. Another good description of a Series 60 is “nimble.” The turning circle is unusually tight for a car of the Cadillac’s size, and this also makes it a fantastic city car, one that is very easy to maneuver through traffic and confined spaces.

Let’s assume that you are arrogant and delusional enough to modify a car like my old Series 60. Let’s say you install a modern, fully independent suspension, disk brakes, power steering and slap in a 327 Chevy V-8. Here’s what you will gain: A higher top speed, a better 0-60 time, improved fuel mileage, quicker steering, and the ease of an automatic transmission. Here’s what you will lose: Your ride will become rougher and bumpier. Your engine will be noisier and will lose a great deal of its hill-climbing ability. Sure it can rocket up the grapevine on I-5, but only with lots of downshifting and extra work. Engine braking and flexibility will be essentially gone, you’ll have to ride the brakes constantly going downhill, and the ability to effortlessly zip up and down winding mountain roads will be diminished. Brakes will be spongier, and though they’ll provide an anti-lock feature, stopping distances will be no better than had they been left stock. It’s even possible that stopping distances will be longer. Steering will be quicker, but most road feel will be lost. Steering effort will be less at very low speeds, but heavier from 5 M.P.H. upwards. Body sway and overall handling will be about the same, though the addition of radial tires will probably result in a lumpier feel. If the car is under-stabilized, lean on hard turns will increase – over stabilized and the car will corner flatter, but body shakes and rattles may result. Hitting the ride/handling sweet spot that the factory achieved will be a daunting task, probably doomed to failure. If a modern set of bucket seats are installed overall seating comfort will decline dramatically, and fatigue on long trips will increase. It needs to be said that most resto-rods are butt-ugly, the aesthetic equivalent of tagging the lobby of the Chrysler Building. Wonderful original cars are too often destroyed to satisfy some owner’s misguided fantasy. The chances of improving on a factory design are miniscule, as anyone with the creative talent to do so would respect what the original builders had accomplished – just as an artist who could paint as well as Rembrandt would never consider getting their hands on one and making “improvements.” The only way that a resto-rod can possibly be justified is if it’s made entirely out of random parts gathered from a scattering of unrestorable parts cars.

Having mentioned how the old Cadillac is much better at going up steep grades than a modern car, it seems an appropriate time to launch into my theory about the difference between torque and horsepower. Not being an engineer, my exclamation should be taken with a grain of salt. To boil it down to a light froth, imagine you’re holding a hammer in your hand. Horsepower is how hard you hit a nail with your hammer – torque is how big and heavy the hammer is. Most modern cars have a healthy amount of horsepower, but their hammers are small and light. In the case of an economy car it’s like trying to pound a nail ferociously with a little tiny hammer more suited for shoe repair. On the other hand, the big classics were like sledgehammers where all it takes is one lazy swing to drive a nail home. My 1937 Cadillac has decent horsepower and a pretty big hammer, which is why it has no trouble climbing hills. In fact, when I’d go up the grapevine on the way to L.A., the old Cad didn’t realize it was climbing a steep grade, we were still on level ground as far as it was concerned. My new Ford truck, on the other hand can, like the Cadillac, go up the grapevine at 70+, but only with a lot of downshifting. Ferraris and Lamborghinis and big old muscle cars are kind of like a bodybuilder wielding a medium size sledgehammer – the kind with a short handle, which can still do an awful lot of damage.

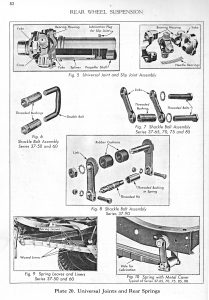

Why is the ride so good on the ’37? There a couple of obvious explanations – a relatively long wheelbase and heavy chassis rails, which conspire to insure that road shocks are pretty well played out by the time they reach the driver. Low pressure, non-radial tires, and fairly gentle spring rates. But there’s another factor, a subtler one. Modern cars utilize rubber or neoprene bushings. To understand how these works, imagine you have a big pencil eraser in your hand. Twist it and it snaps back. Rubber bushings do the same. Their advantage is that they don’t have to be lubricated, and they essentially represent one part – simple and cheap by nature – and low maintenance. What they also do, by “snapping back” is resist. Modern drivers like this, because resistance provides more feedback from the road. Too much, however, can be annoying and exhausting, so there’s an art to striking the right balance – and not all new cars successfully master it. The old Cadillac, on the other hand, uses steel bushings. This sounds harder and harsher, but the reality is the opposite. A steel bushing is very similar to a big bolt in a nut. Imagine sampling one in a hardware store. When well made, the bolt screws into the nut with finger-light effort. Now imagine that the nut and bolt are both heavily greased before being united – the result is NO resistance. What this means on the road is that small imperfections in the pavement go unnoticed, the wheels respond without resistance and the movements are so small as to be undetectable. When the bumps get big, the springs and shocks take over, end of story.

A modern car, with neoprene bushings, resists these tiny road imperfections, and the result is that they’re felt. It’s like punching a well toned boxer in the abs, the blow is absorbed, but felt. On the other hand, the Cadillac responds like a Karate expert, where the opponent’s blow is deflected. Here’s another way of looking at it: imagine a poorly maintained city block where there are 36 lumps and bumps, most of them small, a couple being minor potholes. In a modern, SUV all 36 are felt to one degree or another. Most are barely felt, but they’re there for the counting, should the driver be so inclined. In a luxury barge from the 60’s or 70’s only twelve are felt, the other 24 go unnoticed. In the ’37 Series 60, just 7 are felt. For this, you can thank steel bushings. For the record, in a big Cadillac, a series 75, or even a V-16, 4 to 5 will be felt. The champion in the ride department, is undoubtedly a Model K Lincoln, where no more than 2 bumps are likely to be felt.

Another contributor to gentle riding are the rear leaf springs. When a modern car utilizes leaf springs it installs one or two leaves per rear wheel. On old cars many leaves are used, anywhere from seven to sixteen. I’m not an engineer, but I’m guessing that multiple leaves allow for spring action to be carefully tuned for varying road conditions – soft response on smooth pavement increasing to firmer resistance on rough roads. If only one leaf spring is used, or one coil spring, this spring has to do dual or triple duty, which has obvious limitations.

Why are the seats so comfortable? The 1937 Cadillac utilizes Marshall springs – another word for coil springs. These are wrapped in cloth and attached to a wooden frame, which is good for absorbing shocks. Then the surface level is stuffed with cotton.

In contrast, modern cars use flat springs, (cheap with limited flexibility,) and molded foam rubber rather than cotton. It’s the difference between an upholstered dining chair in a decent restaurant and an over-stuffed living room sofa.

So what are the flaws of a 1937 Series 60? Start with fuel consumption, which is a reliable 13 m.p.h. – city or highway, it doesn’t matter – it’s going to be 13 m.p.h. On the other hand, the engine was built for 77 octane regular, so it can probably run on ant piss, or anything moderately combustible. However, certain modern fuels can corrode gaskets and brass parts, so additives are needed.

There’s no air-conditioning – no power windows – no power seats, or anything for that matter. On the other hand, there’s less to go wrong – and the simple ventilation system is really effective, as are the broadcloth seats, which breathe on a hot day.

The gauges never falter, but the electric clock will last for about a week.

Vapor lock. I got it rarely, but it’s there, lurking. Measures can be taken, but like hurricane shutters, only so much can be done if things really get bad.

Tune ups. The 346 V-8 is very easy to tune and maintain by the standards of its time, and the payoff of a perfectly timed, sweet running engine is wonderful. But electronic ignition and fuel injection is still better.

Maintenance. If you love working on cars, you’ll be in heaven. A 1937 V-8 Cadillac is far from temperamental and finicky, you can neglect routine maintenance for years and it will keep soldiering on and driving more or less like a Cadillac. But change the oil regularly, lube it like the factory recommends every 1000 miles or so, check the tires, top off the cooling, etc., etc. and the damn thing will last forever. Actually, you can double or triple the recommended schedule because modern oils and coolants are far superior to what was available in the thirties – but be very sure to use the right stuff. Unleaded fuel and certain motor oils will poison the engine. Fortunately, valves can be reconfigured to run on unleaded and the proper lubricants are available – just do your research.

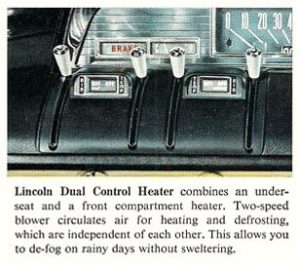

The heater and defroster system, one of the earliest to be offered in an automobile, is comical, to say the least. Does it work? yeah, kind of like castor oil for a malady, I suppose. The heater has a couple of blower speeds, but the only way to moderate the temperature, is to open or close little doors on the heater, which sits below the dash. The result is that the driver’s compartment gets really hot, really fast, and the only solution is to turn the heater off or open the windows. The front vent windows also must be opened if complete windshield defrosting is required, as the vents above the dash only clear a semicircle in front of the driver and the passenger, and the side windows fog up swiftly.

Vacuum windshield wipers – need I say more.

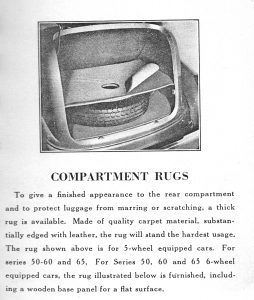

Limited trunk space – but at least it has one.

Air pollution. No smog control – no catalytic converter. I do wonder if that long stroke creates more complete combustion and less smog. Back in the 70’s I got stopped by an impromptu police checkpoint, where all cars were stopped and a probe was stuck up their exhaust to check for pollution. Of course, the standards of the 70’s weren’t as strict as today’s, but a checkpoint suggested that the powers that be had gotten serious. The old Cadillac hadn’t been tuned in a while and was a far way from being fully restored; nonetheless it passed, to the surprise of the local constabulary.

No seat belts or air bags. Then again, after market seat belts can be installed, and to the Cadillac’s credit no modern car would want to be on the receiving end of a collision. I heard a story about a 1939 Cadillac that had an unfortunate encounter with a stone retaining wall. The Cadillac received a grapefruit sized dent in one of its front fenders – the wall had to be replaced. A more extreme account came to me from Jack Passey, retelling a dramatic evening he experienced back in the ’50’s while piloting a 1933 Cadillac V-16 Seven Passenger Sedan. On California’s Highway 17, a notorious deathtrap, he had a ’55 Chevy pull in front of him from a side road. He slammed on the brakes, started to slide off the road, and head for a cliff, said to himself “what the hell, ” let up on the brakes and smashed into the rear of the Chevy instead – crumpling the trunk all the way up to the rear window. No one was hurt, pertinent information was exchanged, and Jack went on his way. A few minutes later, the same thing happened, this time the recipient being a 1948 Chrysler, which was also rendered trunkless by Jack’s V-16. Once again there were no injuries and information was exchanged. It should be noted that a ’55 Chevy is a substantial car by contemporary standards – a ’48 Chrysler even more so.

I asked Jack what damage had been done to the V-16, which was conveniently parked a few feet away. Jack walked over to the Cadillac and pointed to the front bumper – “Do you see that scratch there on the left?” I nodded my head politely, but must confess that I didn’t see any damage at all. In fairness, the 1933 V-16 is probably the most formidable car that Cadillac every built, it would easily intimidate a Hummer.

That said, all Cadillacs from the Classic Era are not cars you’d want to go head to head with today.

Weirdly, the narrow tires are really good on a rainy road. I think it’s because there’s less surface to be coaxed into hydroplaning. Despite this, stopping distances don’t suffer. I know it sounds odd, but even with the miserable defroster, the awful vacuum wipers, and the low-illumination headlights, I always felt very safe and relaxed in the big old Cadillac when it had to plow through a storm. It was more reassuring than many other cars that I’ve driven under such conditions, and that includes new ones. Go figure.

WAR STORIES

I bought my ’37 Series 60 from Jack Passey when I was sixteen. He pulled it out from one of his sheds at his old Bascom Avenue location, and it was waiting for me when I arrived around four in the afternoon, after school. The Cadillac needed paint and a muffler, it made a hell of a racket when revved, but it ran. My dad came with me, and I think he drove the Cadillac eighty percent of the way, then turned it over to me at the bottom of the steep hill that led up to my mom’s house. I’d never driven a car with a manual transmission, and I had to learn on the spot – the results were pretty ugly. Typically, my first attempts ended with my stalling the car in the middle of the narrow winding road that made its way up to my mom’s. No surprise, as I made my third attempt to coax the car forward, another car appeared behind me and honked its horn impatiently. Okay, I hadn’t given the car enough gas, and I had to get out of the way – so the solution was to give the Cadillac lots of gas. I revved the engine to about 2,500 r.p.m. and let out the clutch, or more appropriately, popped it because I hadn’t mastered the art of letting it out slowly. What happened was a surprise to no one but myself. The car leapt forward, burning rubber, and heading for the stone edge of a small bridge. I turned the car hard to the right, darting into a private road, which culminated in a very swiftly approaching dead end. I slammed on the brakes right before hitting a wall, and of course, the car stalled. The impatient driver, followed behind me, very cautiously and slipped into a driveway – this time they didn’t honk.

I have no idea how I ever managed to back out and get up the hill. I almost didn’t make it – when nearly home, I backed off the road onto a steep dirt driveway. I succeeded in leaving the dirt, ending up in high, dried grass, which offered as much traction as wet glass. Each time I tried to go forward, the car slipped backwards. By some miracle, I extracted myself, though I can no longer remember what the miracle was.

I used the Cadillac to motor to high school, and though it got some attention, old cars weren’t that uncommon in the sixties, so it hardly made me a celebrity. It did, however, get the once over from a very unusual classmate. Fred Woods, who was my age, went on to kidnap 26 school children near the town of Chowchilla, aided by two more classmates, the Showenfeld Brothers. One morning, as I was climbing out of the Cadillac, Fred came up to me and smiled, looking not unlike the bad guy in “The Heat Of The Night,” which had recently been released.

“Nice car,” he said.

“Thanks.” I answered.

“Say,” he asked, still smiling, “do the doors make any noise when they close?” He laughed, softly, and headed on to class.

It’s common, when someone is revealed to have committed some terrible criminal act for their friends to say, “He’s the last person I would ever have thought could do such a thing.” Not so Fred Woods, at least in my opinion, from the first time I saw him I thought, “He looks like the kind of guy who’s going to kidnap 26 school children someday.”

The old Cadillac needed a lot of repairs to make it school ready. A very competent local garage relined all the brakes and turned the drums, installed a new exhaust system, and replaced the entire steering unit. I found a box and column from a junked ’37 Buick Special in a local yard and handed it over to them. The unit was identical to the one in my Cadillac, though the Buick’s had a steering lock. A number of other repairs were performed so that the car was safe and reliable. The black wall truck tires that the car had when I got it were replaced with 6 ply wide whitewalls. They looked great, but did little to improve ride or handling. Years later I was able to purchase a set of reproduction Firestone 4 ply tires, which were made from the original molds used back in 1937. These were the exact tires that car was equipped with when it was brand new and the difference was astounding. The ride became 50% smoother and the steering was rendered about 70% lighter.

In the early 70’s I had a pretty adventurous road trip in a 1959 Edsel, returning it from my east coast college in the summer. The Edsel lived up to its reputation by blowing a head gasket and leaving me stranded for a week in the town of Floodwood Minnesota. Once it was repaired, I headed west and rendezvoused with friends at the base of the Sierras, (Nevada side.) They met me in the Cadillac. We traded cars, and began the long steep climb to the summit. The Cadillac was displeased with the climb and kept discharging water through the overflow tube, causing the temperature to rise. I solved the problem by converting the non-pressurized system to a pressurized one by jamming a rag under the cap and cutting off the overflow – problem solved.

Several hours later we all stopped at Vallejo to get gas, and the Edsel lit out first. Perhaps because I was adding water, or maybe because the Cadillac was so low on gas, whatever the reason, it wasn’t until twenty minutes after my friends’ departure that I got back on the highway. I was kind of annoyed and determined to catch them, so I simply put my foot all the way to the floor and kept it there. Rush hour had begun; however, as rush hour in those days was nothing like today, I was still able to make good time by moving in and out of lanes with a high degree of recklessness. The needle on the Cadillac’s speedometer pegged itself at 110, and that’s where it stayed for the twenty minutes it took me to catch up to my friends, (who were doing 70,) just as they were entering the toll plaza for the Bay Bridge. The Cadillac didn’t seem to mind the workout, though it did get “a little light in its loafers” over 90 m.p.h.

I pulled a similar stunt a year or two later, driving out to the beach on a lonely stretch of highway late one night. The road was smooth with gentle curves and the Cadillac went right up to the indicated 110, (probably an exaggeration on the car’s part – but still damned fast,) and, as before, the ride was fairly unnerving and uncontrolled. Years later, I discovered that some crucial elements of the suspension were not as they should have been for either of these speed tests, and I feel strongly that a brand new 1937 Series 60 would have been far more steady and reassuring at very high speeds.

One example of the car’s legendary quality came when I was driving from San Francisco to Cupertino for some regular maintenance – a distance of about 50 miles. The car had around 250,000 miles on it and the water pump froze up. This snapped a fan belt so that I also lost the generator. I stopped, appraised the situation, discarded the broken belt and soldiered on, figuring I’d call a tow truck when the temperature started to rise or the engine began to fade. This, however, never happened, the Cadillac continued on as if everything was normal, the temperature never getting out of the cold range. I arrived at the shop on schedule and without any fuss.

I never fully restored my Cadillac, just did what was needed to keep it functioning. It got a new paint job early on and the engine was completely rebuilt at around 300,000 miles. The water pump, radiator, generator, voltage regulator, etc. all needed attention at some point or another. After being forced off the road one dark and stormy night and only avoiding a plunge over a cliff because the rear wheel lodged on a rock, it was necessary to replace one of the rear spring shackles and a bent front steering knuckle support.

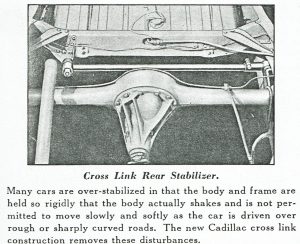

The old beast always drove well, but never reached anything approaching perfection. The handling was good, but it leaned a lot on corners and under hard acceleration, the rear end would squat down. According to a salesman’s reference book it had a rear cross link unit that was touted to prevent both of these things from happening. For years, I assumed that the book played up primitive, not very effective engineering. As time went by, however, I started to wonder. If this cross link was such a lame design, why did Cadillac use it well into the fifties? Besides, a friend’s low mileage 1938 V-16 used the same device, and that car barely leaned while cornering hard. Numerous times I crawled under my Cadillac to inspect the unit, and it seemed fine, though it didn’t help that I could never figure out exactly how it worked. Finally, after a number of years, I decided to spruce up the suspension, and started by replacing the rubber bushings on the rear cross link. As I dismantled it, I quickly discovered that a critical nut securing one side of the unit to the frame was completely missing. What this meant is that for all the years that I owned the car, the cross link was completely non-functional.

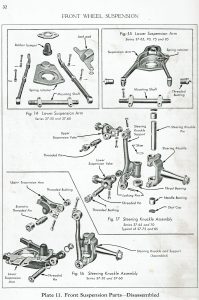

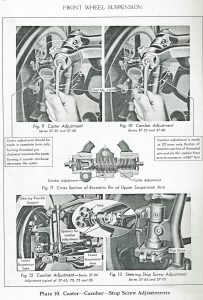

I moved on to have the front shocks rebuilt, learning that one was also not working at all. Unlike a modern car, these shocks double as the upper control arm, so their proper functioning is pretty important. I adjusted the steering box so that the annoying half-inch of play all but disappeared and replaced the bushings on the front anti-sway bar. The most critical part of this job is to be sure to install new rubber bushings where the sway bar bolts to the front cross-over plate – otherwise you’re essentially revarnishing deck chairs on the Titanic. Once all the changes were made, I took the Cadillac out for a test drive. All the lean was gone and there was no tendency for the rear to squat down during hard acceleration – a very pleasant car to drive had become one of the nicest vehicles I had ever piloted.

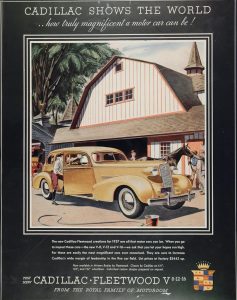

There was a tremendous lineup of models in 1937. The small Series 60 was offered as a sedan; there were also two coupes, a convertible coupe, and a convertible sedan.

Then came the Series 65, a sedan only, which bridged the gap between the 60 and the far more expensive Fleetwood bodied Series 70.

The top of the line V-8s were the Series 75.

After that was the Series 85, which offered all the Series 75 bodies with a V-12 powerplant.

Finally, the Cadillac pinnacle was reached with the Series 90, the legendary V-16. I only drove one ’37 V-16, a seven passenger sedan, and the experience was unforgettable.

A number of small cars drive like big cars, (not always a virtue,) while a select few big cars drive like small cars – the Cadillac V-16s, at least, the later ones, fall into this category. The ride, of course, is strictly big car, a V-16 is impervious to nearly all road flaws. The handling, however, is astonishingly nimble, and the nearly 20 foot long behemoth can be maneuvered about with ease and agility. Steering isn’t especially heavy, brakes, power assisted, are excellent, and comfort is outstanding. The second generation V-16s, which debuted in 1938, were even better – I would rate this model of V-16 as one of the finest driving cars I have ever encountered.

Ironically, it was the low rent models like my Series 60, which doomed great classics such as the V-16. Automotive engineering had advanced so much in the seven odd years since the twenties crashed into depression that a car like the Series 60 could do nearly everything expected of a V-16. It rode nearly as well, handled better and was probably faster. It was much cheaper to operate and far easier to maintain, and the quality, if not the best money could buy, was nonetheless damned good.

A perfect example of what superb motorcars these Cadillacs were is recounted in the Automobile Quarterly history of Cadillac published in 1987. According to David Scott-Moncrieff “A friend of mine left his hotel in Switzerland, and drove his Bugatti as fast as he could to Paris. As he drew into the Liotti, grimy and exhausted, he was followed by a chauffeur driven Cadillac containing two American matrons. They and their chauffeur were as fresh as paint and showed no signs of fatigue. They had been staying at the same hotel as my friend in Switzerland, and had left it an hour after he did!” This story illustrates how Cadillacs in the thirties were well ahead of their time, providing a swift, effortless, comfortable and reliable motoring experience. They were truly the Standard Of The World, and have aged so well that if I had to take a long road trip and was offered a choice between my old ’37 and a brand new Mercedes it would be no contest – I’d take the Cadillac in a heartbeat.

SPECIFICTIONS AND FACTORY DELIGHTS